Let Light Fly the Sparks

Landmark Light Experiments Revisited

There’s something ironic about light.

Unlike other physical phenomenon, it seems pretty intuitive.

For we primarily rely on vision to sense our environment.

Yet, for the longest time, light had remained the least understood concept in all of physics.

And despite all the work that has happened in the last couple of centuries, its nature and dynamics still amaze us to this day.

So today, we will revisit the key developments in the study of light.

These are experiments which radially altered our notion about the same.

Newton’s Prism

Isaac Newton graduated from Cambridge University’s Trinity College in 1665.

The Great Plague had just struck London.

So, he returned to his family’s farm in the countryside and began investigating the nature of color.

At the time, the world of optics was fertile with unexplained observations.

Robert Hooke and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek had recently succeeded in building high quality microscopes. The refraction of sunlight into colors by a prism had been observed but was not understood.

The generally consensus was that the ‘pure’ white light was contaminated by ‘gross matter’ to yield colors.

Refraction of White Light by Prism

Newton began by cutting a pinhole in his window shade.

This pinhole let in sunlight, which showed up on his wall as a round illuminated area.

Refracted by a prism, it turned into an oblong area with a rainbow of colors.

Intrigued by the change in shape, Newton cut a variety of holes of different sizes and shapes.

Yet, regardless of the shape of the original beam, the refracted light turned more oblong. Newton also placed a second prism of the same type in the path of the light.

Surprisingly, this turned the colors back into white light.

This experiment of Newton proved that white light wasn’t ‘pure’. Instead, it consisted of a spectrum of colours which combined to form the white light.

Isolating Colours

After coming to this conclusion, Newton tried to isolate the light of each colour.

He drilled a small hole onto a piece of wood. Then, by refracting the light on wood, a beam of light of pure colour was obtained.

To check if these colours were themselves pure, Newton repeated what he had done with white light - passing them through a prism.

He was able to show that blue light, for instance, when refracted through a second prism yielded again only blue light.

Similarly, red light yielded only red light.

Moreover, the angle at which light was deflected onto his wall was dependent on the color.

In Newton’s terms, dfferent colors of light had different degrees of ‘refrangibility’ (which we now refer to as the refractive index)

This was an inherent property of light of that color.

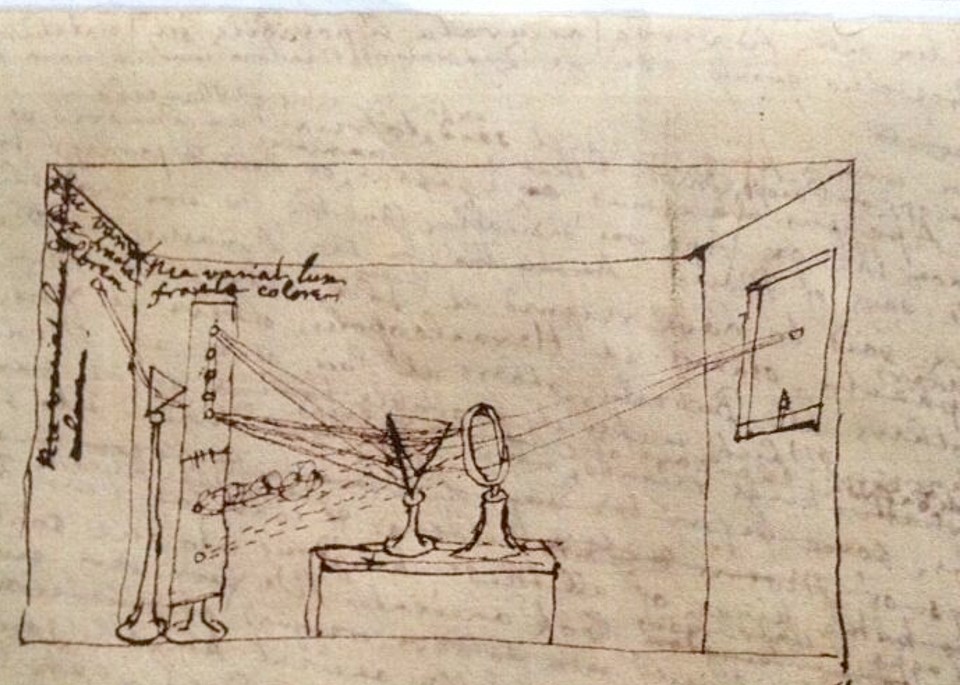

Newton’s drawing of his prism experiment

(Source : https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/newtons-prism-experiment-0)

Newton was pathetically slow at publishing.

For instance, his New Theory of Light and Colors did not appear in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society until 1672.

Robert Hooke was a quite influential member of the Society. Given his own theories of colour, the publication set off a feud between the two intellectual giants.

This goes to show, that even though the community of scientists in the seventeenth century was a small one, it was no less different than what it is today.

Romer’s Determination of the Speed of Light

In the 17th century, light presumed to be infinitely fast.

So, nobody was really interested in measuring the speed of light at the time. Likewise, even Roemer was not looking for light speed when he found it. Instead, he was working at the Paris Observatory, compiling extensive observations of the orbit of Io.

Io is the innermost of the four big satellites of Jupiter discovered by Galileo in 1610.

By timing the eclipses of Io by Jupiter, Roemer hoped to determine a more accurate value for the satellite’s orbital period.

But, let us not get ahead of ourselves.

Discrepancy in Io’s orbital period

The story starts not with Roemer, but Cassini.

Before coming to Paris in 1669, Cassini had spent a considerable amount of time and effort on investigating the motions of the satellites of Jupiter. He published the first reasonably accurate tables of the motions of these satellites in 1668, which he had further refined by 1693.

In 1675, Cassini found an inequality in the motion of Io.

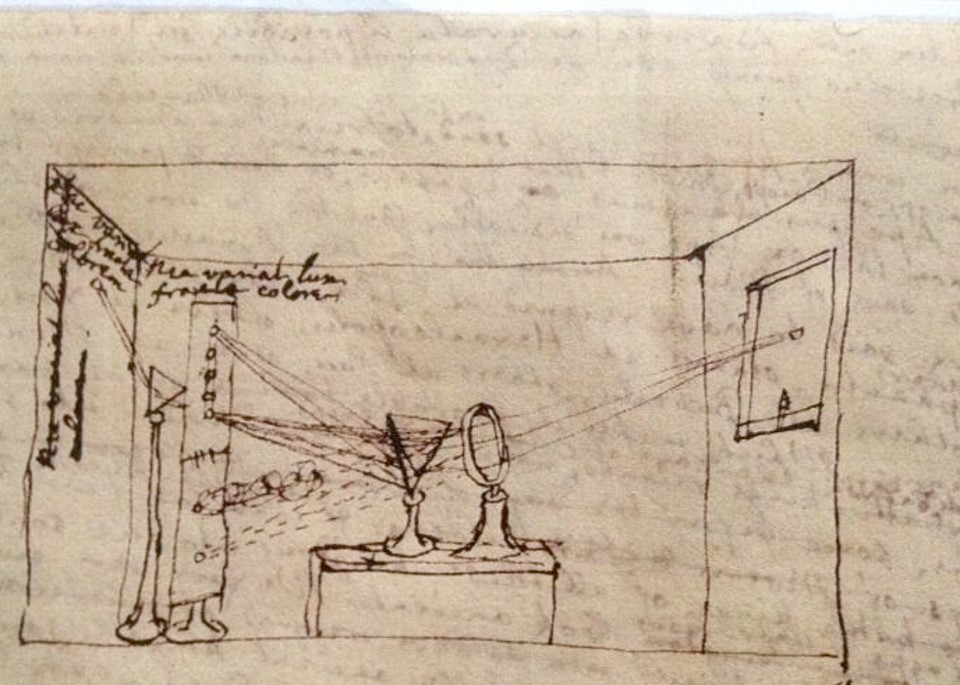

Surprisingly, this inequality was heavily correlated with the distance between Earth and Jupiter. Io is eclipsed by Jupiter once every orbit, as seen from the Earth.

The time interval between successive eclipses became steadily shorter as the Earth in its orbit moved toward Jupiter and became steadily longer as the Earth moved away from Jupiter.

These differences accumulated, and showed up in his measurements.

Roemer, who was also working in Paris Observatory at the time, took up the problem.

From the data, Roemer estimated that when the Earth was nearest to Jupiter, eclipses of Io would occur about 11 minutes earlier than predicted based on the average orbital period over many years.

And 6.5 months later, when the Earth was farthest from Jupiter, the eclipses would occur about 11 minutes later than predicted.

When the Earth is at E2, the light from the Jupiter system has to travel an extra distance represented by the diameter of the Earth’s orbit. This causes a delay in the timing of the eclipses.

The currently accepted orbital period of Io is 1.769 Earth days.

Using his calculations, he estimated the extent of this effect on the eclipse of Io on 9 November 1676.

Roemer’s hypothesis caught the attention of scientists across Europe.

Linking difference in orbital period to the speed of light

Roemer knew that the true orbital period of Io could have nothing to do with the relative positions of the Earth and Jupiter.

Roemer’s genius insight was realizing that the time difference must be due to the finite speed of light. This was way ahead of his time, considering the dominant view of infinite speed, vigorously argued by Descartes.

The rationale is, light from the Jupiter system has to travel farther to reach the Earth when the two planets are on opposite sides of the Sun than when they are closer together.

Roemer estimated that light required 22 minutes to cross the diameter of the Earth’s orbit.

The speed of light could then be found by dividing the diameter of the Earth’s orbit by the time difference.

The value came out to be about 225,000 km/s (140,000 miles/s) - a good approximation of the currently accepted value of 299,792.458 km/s (186,282 miles/sec).

Young’s Double Slit Experiment

The nature of light was a matter of serious debate among 17th century scientists.

There was evidence for both opposing views - the Corpuscular (Particle) theory of Newton and the Wave theory of Huygens. But, given the influence of Newton in physics, it was nearly impossible for anyone to dispute his theory.

All of this changed in 1801.

In 1801, Thomas Young presented a serious challenge to Newton’s ideas on the nature of light. Young had first read Newton’s Opticks in 1790 at age 17. Though he admired Newton’s work, by 1800 Young saw some problems with Newton’s corpuscular theory. For instance, he noticed that at interfaces such as that between air and water, some light is reflected and some is refracted, but the corpuscular theory can’t easily explain why that happens. The corpuscular theory also had trouble explaining why different colors of light are refracted to different degrees.

So, Young began thinking on the lines of the Wave theory.

A familiar wave is sound. Sound is a compression wave in air. Thus, Young began finding similarities between light and sound. He noticed that when two waves of sound cross, they interfere with each other, producing beats. Slowly, he began to realize that light might exhibit interference phenomena as well (optical equivalent of beats).

In May of 1801, Young came up with the basic idea for the double-slit experiment to demonstrate the interference of light waves which now carries his name.

The demonstration would provide solid evidence that light was a wave, not a particle.

In the first version of the experiment, Young actually didn’t use two slits, but rather a single thin card.

He covered a window with a piece of paper with a tiny hole in it. A thin beam of light passed through the hole. He held the card in the light beam, splitting the beam in two. Light passing on one side of the card interfered with light from the other side of the card to create fringes, which Young observed on the opposite wall.

Interference pattern formed in Young’s Double Slit Experiment

Young also used his data to calculate the wavelengths of different colors of light, coming very close to modern values.

Ill Reception of Young’s Research

In November 1801, Young presented his paper, titled “On the theory of light and color” to the Royal Society. In that lecture, he described interference of light waves and the slit experiment. He also presented an analogy with sound waves and with water waves, and even developed a demonstration wave tank to show interference patterns in water.

Despite Young’s convincing experiment, people didn’t want to believe Newton was wrong.

A disappointed Young wrote in response to one critic

‘Much as I venerate the name of Newton, I am not therefore obliged to believe that he was infallible’

The basic double-slit setup Young proposed has since been used not only to show that light acts like a wave, but also to demonstrate that electrons can act like waves and create interference patterns. Since the development of quantum mechanics, physicists know that light is both particle and wave, not simply one or the other.

Michelson Morley Experiment

Despite having firmly established the wave nature of that light is a wave, young’s experiment didn’t answer a major question.

What exactly is waving ?

Like when a sound wave passes, the material—air, water or solid—waves as it goes through.

This is what Michelson sought to find out after his iconic measurement of the speed of light in 1879.

He had nailed the measurement to be 186,350 miles/s to an accuracy of around 30 miles/s. This measurement was made by timing a flash of light travelling between mirrors in Annapolis, And, it agreed well with less direct measurements based on astronomical observations at the time.

Taking hint from the nature of sound propagation, it was natural to suppose that light must be just waves in some mysterious material.

This exotic medium was called the aether.

It was believed to permeate everywhere, surrounding everything we see. Aether was also expected to fill all of space, out to the stars.

This is because to see them the medium must be present to carry the light all the way from stars to the Earth.

Some properties of this alleged medium could be inferred based on the existing knowledge about light. Since light travels so fast, it must be very light, and very hard to compress. Yet, it must allow solid bodies to pass through it freely, without aether resistance. Otherwise the planets would have been slowing down.

Thus, it could be pictured as a ghostly wind blowing through the Earth.

All these were just speculations. To prove this hypothesis the presence of ‘aether wind’ had to be detected.

Detecting the ‘Aether Wind’

Naturally, something that allows solid bodies to pass through it freely must be very hard to detect.

But Michelson realized that, just as the speed of sound is relative to the air, so the speed of light must be relative to the aether.

So, if you could measure the speed of light accurately enough, you could measure the speed of light travelling upwind, and the speed of light travelling downwind.

If the wind were present, the difference of the two measurements should be twice the windspeed.

In principle, it seems achievable.

But implementing it is a totally different ball game.

All the recent accurate measurements had used light travelling to a distant mirror and coming back.

So, if there was an aether wind along the direction between the mirrors, it would have opposite effects on the two parts of the measurement. This would leave a very small overall effect.

Thus, there was no technically feasible way to do a one-way determination of the speed of light (upwind or downwind separately).

The Puzzle that inspired the Experiment

After thinking about this issue, Michelson came up with a clever idea for detecting the aether wind.

As he explained to his children (according to his daughter), it was based on the following puzzle:

Suppose we have a river of width 100 feet, and two swimmers who both swim at the same speed 5 feet per second. The river is flowing at a steady rate of 3 feet per second. The swimmers race in the following way : they both start at the same point on one bank. One swims directly across the river to the closest point on the opposite bank, then turns around and swims back. The other stays on one side of the river, swimming upstream a distance (measured along the bank) exactly equal to the width of the river, then swims back to the start. Who wins?

Consider first the swimmer going upstream and back.

Going 100 feet upstream, the speed relative to the bank is only 2 feet per second, so that takes 50 seconds. Coming back, the speed is 8 feet per second, so it takes 12.5 seconds, for a total time of 62.5 seconds.

The swimmer going across the flow is trickier.

Simply aiming directly for the opposite bank will not work, for the flow will carry the swimmer downstream.

To succeed in going directly across, the swimmer must actually aim upstream at the correct angle.

In this specific case, the swimmer is going at 5 feet per second, at an angle, relative to the river, and being carried downstream at a rate of 3 feet per second. If the angle is correctly chosen so that the net movement is directly across, in one second the swimmer must have moved four feet across.

That is to say, the distances covered in one second will form a 3,4,5 triangle. So, at a crossing rate of 4 feet per second, the swimmer gets across in 25 seconds, and back in the same time, for a total time of 50 seconds.

So, the cross-stream swimmer wins.

Translating Puzzle to Reality

Well OK, you say.

What does any of this have to do with the ‘aether wind’ ?

Interestingly, the result turns out to be true regardless of their swimming speed.

Thus, if a cross-stream swimmer swimming at the speed of 5 feet/s would win from his counterpart, so would a cross-stream swimmer swimming at 186,350 miles/s.

Of course, swimming at such incredible speeds is far beyond anyone’s physical capabilities (as far as we know !).

But we don’t need real swimmers in a river to test the results.

Light pulses ‘swimming’ in aether would do just fine.

And this was Michelson’s incredible feat.

He constructed an exactly similar race for pulses of light, with the aether wind playing the part of the river.

Design of the Experiment

The scheme of the experiment is as follows.

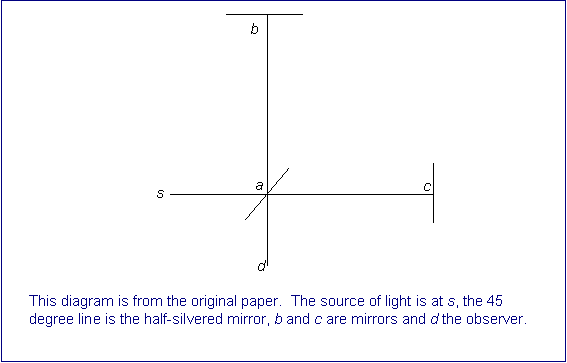

Schematic diagram of the apparatus used in Michelson-Morley experiment

(Source : http://galileoandeinstein.physics.virginia.edu/lectures/michelson.html)

A pulse of light is directed at an angle of 45 degrees at a half-silvered, half transparent mirror. So, that half the pulse goes on through the glass, half is reflected.

These two half-pulses are the two swimmers. They both go on to distant mirrors which reflect them back to the half-silvered mirror. At this point, they are again half reflected and half transmitted, but a telescope is placed behind the half-silvered mirror.

By similar reasoning as initially stated, half of each half-pulse will arrive in this telescope.

Now, if there is an aether wind blowing, someone looking through the telescope should see the halves of the two half-pulses to arrive at slightly different times, since one would have gone more upstream and back, one more across stream in general.

To maximize the effect, the whole apparatus, including the distant mirrors, was placed on a large turntable so it could be swung around.

On turning it through 90 degrees, the upstream-downstream and the cross-stream waves change places. Now the other one should be behind. Thus, if there is an aether wind, if you watch through the telescope while you rotate the turntable, you should expect to see variations in the brightness of the incoming light.

In the actual experiment, to magnify the time difference between the two paths, in the actual experiment the light was reflected backwards and forwards several times, like a several lap race.

Aether Debunked

Michelson calculated that an aether windspeed of only one or two miles a second would have observable effects in this experiment.

So, if the aether windspeed was comparable to the earth’s speed in orbit around the sun (30 km/s or 18.6 miles/s), it would be easy to see.

But sadly, nothing was observed.

Yes, absolutely nothing. The light intensity did not vary at all.

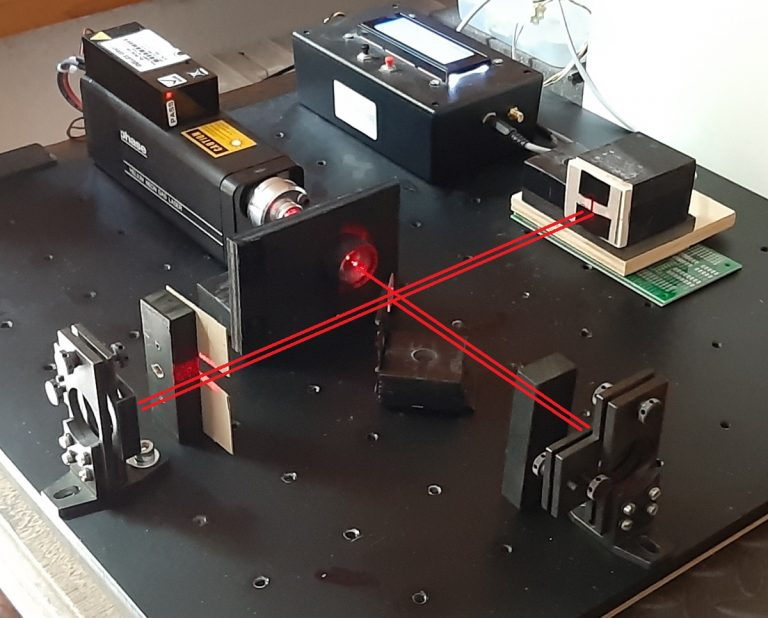

Interferometer used in Michelson-Morley experiment

(Source : https://physicsopenlab.org/2020/05/16/michelson-morley-interferometer/)

Later, the experiment was redesigned so that an aether wind caused by the earth’s daily rotation could be detected.

Again, nothing was seen.

Finally, Michelson wondered if the aether was somehow getting stuck to the earth, like the air in a below-decks cabin on a ship.

So, he redid the experiment on top of a high mountain in California.

Again, no aether wind was observed.

Even in principle, it was difficult to believe that the aether in the immediate vicinity of the earth was stuck to it and moving with it, because light rays from stars would deflect as they went from the moving faraway aether to the local stuck aether.

Failure after failure in detecting any meaningful results led to only one possible conclusion.

The concept of an all-pervading aether was plain wrong !

Now we know from Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism that light is really just an electromagnetic wave.

In the 1860’s Maxwell had written down a set of equations describing how electric and magnetic fields can give rise to each other. Moreover, he had discovered that his equations predicted there could be waves made up of electric and magnetic fields.

The speed of these waves, deduced from experiments on how these fields link together, would be 300,000 km/s.

A coincidence too good to be true.

Initially, light being an electromagnetic was just seen a natural assumption.

But, subsequent experiments have confirmed that light is truly the result of fast-varying electric and magnetic fields.

And this put all the concerns regarding the existence of a medium for light propagation to rest.

References

- https://www.aaas.org/isaac-newton-and-problem-color

- https://www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/cosmic-horizons-book/ole-roemer-speed-of-light

- https://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu//full/1983JHA….14..137V/0000138.000.html

- https://www.aps.org/archives/publications/apsnews/200805/physicshistory.cfm

- http://galileoandeinstein.physics.virginia.edu/lectures/michelson.html